API Docs with Sphinx

by Bill Jellesma2018-09-22 23:00:00

TL;DR

- I've found API documentation very useful to help me to understand other people's work as well as my own once it's become really big and I've forgotten what functions I've created.

- Sphinx works by taking my docstrings and putting them into easily searchable webpages.

- The magic of Sphinx occurs when the autodoc extension is used. This is what will generate your API documentation based on your docstrings

Making API Documentation Simple with Sphinx

Some questions I find that I'm always asking myself either when using a new library/framework or even using my own projects are what functions do I have available to me or what types of parameters does this function expect. In the case of my own projects, I always find myself getting into the mindset of "Oh, I'll remember that this function exists because I wrote it." But what happens when that project gets more classes and functions? Or what happens when you focus on another project for awhile and then come back to your original project? The same outcome happens, you forgot what functions you've written, what you've named those functions, and what parameters it needs. Now, instead of building in those new features, you're forced to spend some amount of time and energy meticulously scrolling through your own code. Along comes the concept of API documentation.

Last week, I wrote an article on using markdown to write documentation for yourself and for other developers. Markdown works great for documenting what's involved in the project in the "story" type format we're used to reading. API documentation is more technical documentation for how to use and extend the functionality that already exists.

There are many document generation programs out there specifically for API documentation, but one program that I've found especially useful is Sphinx.

Enter the Mythical Cat

When I started working on larger projects, remembering the specifics of the functions was a nightmare. I would frequently make a new function that would do almost the same action as an already existing function and then when I noticed, I couldn't delete the old one because I'm not sure what else is depending on the call to that function. When I started using Sphinx, the only thing I had to remember was to just spend an extra minute or two writing a docstring within my function. Here's where Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) comes into the story. PEP provides suggestions for standardizing your code so that it is easier to read for yourself and other developers. For my docstrings, I've personally found it helpful to make a boilerplate docstring that is a variation on PEP 257 that I can copy and paste whenever I make a new function, module, or class:

<function description>

Args: <argument> (<required>) - <data type> - <argument description>

<argument> (<required>) - <data type> - <argument description>

...

Return: <data type> - <return description>Although this boilerplate docstring is built for functions, it can be modified for modules and classes. Everything in angle brackets are variables and will differ based on that specific function. An example of this docstring for:

def dummy_function(req, opt="I gotta have more cowbell"):

new_number = req + 1

return new_numbercould be

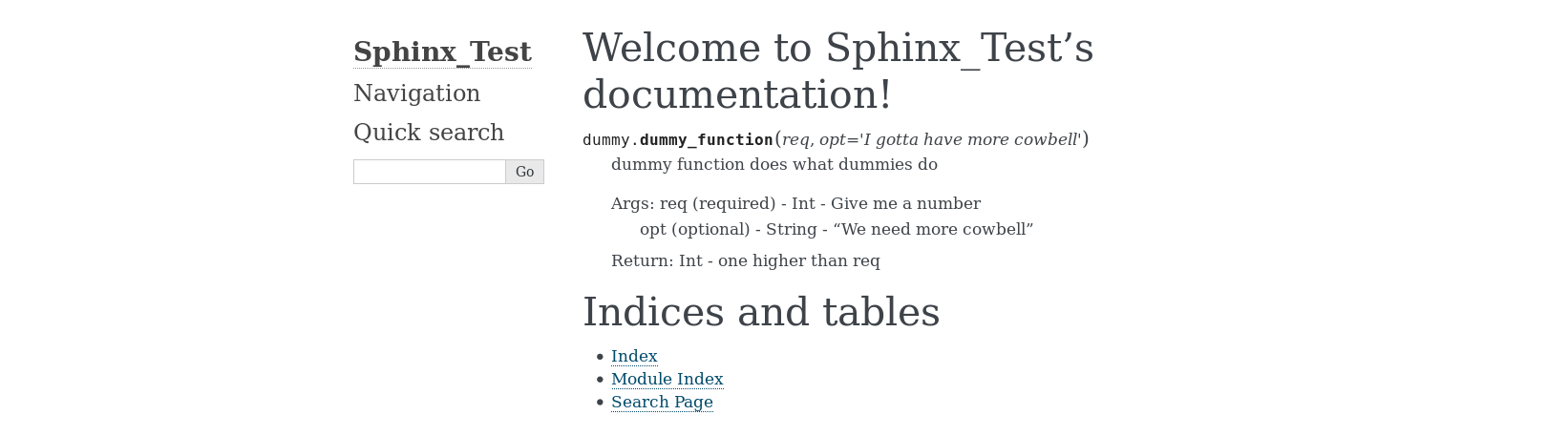

dummy function does what dummies do

Args: req (required) - Int - Give me a number

opt (optional) - String - "We need more cowbell"

Return: Int - one higher than reqOften the hardest part is when you're in the middle of trying to make a new feature for your program and then remember that it'll be best in the long run to slow down and make the necessary docs before you forget.

Though there are a lot of documentation generators out there, Sphinx is a fairly well known and popular one. Serveral open source projects use Sphinx including Flask, A lightweight but powerful microframework for creating web applications. A full list of projects using Sphinx is available at their official website

Start the Machine

Sphinx may take a bit of effort to get started and have a bit of a learning curve but, once Sphinx is understood, you'll wonder how you ever wrote code without it. Sphinx installation has a little bit different ways of starting for Linux vs. Windows. I'll start with Windows.

Windows

The following steps assume that you have python already installed to your machine. When using Windows, I typically use git bash to add some bash flavor to Windows.

- Optionally, you may want to create a virtual environment to compartmentalize this code rather than installing it to your entire system. I like using

virtualenvfor its lightweight and easy setup.

$ virtualenv sphinx_test_env

$ source sphinx_test_env- Install Sphinx. If you are using a virtual environment, this installation will only apply to that environment and not your system as a whole.

pip install sphinxLinux

Simply download Sphinx from your package repository:

Debian/Ubuntu: apt-get install python-sphinx

RHEL/CentOS: yum install python-sphinx

Other

Other instructions are available from the official documentation

Back to Quickstart

- Navigate to your directory and use the Sphinx quickstart CLI module to quickly get up and running.

sphinx-quickstart- The CLI will ask you several questions about your installation. You can accept the default for all options except for the autodoc extension, which we gravely desire!

$ sphinx-quickstart

Welcome to the Sphinx 1.8.0 quickstart utility.

Please enter values for the following settings (just press Enter to

accept a default value, if one is given in brackets).

Selected root path: .

You have two options for placing the build directory for Sphinx output.

Either, you use a directory "_build" within the root path, or you separate

"source" and "build" directories within the root path.

> Separate source and build directories (y/n) [n]:

Inside the root directory, two more directories will be created; "_templates"

for custom HTML templates and "_static" for custom stylesheets and other static

files. You can enter another prefix (such as ".") to replace the underscore.

> Name prefix for templates and static dir [_]:

The project name will occur in several places in the built documentation.

> Project name: Sphinx_Test

> Author name(s): Tester

> Project release []: 1

If the documents are to be written in a language other than English,

you can select a language here by its language code. Sphinx will then

translate text that it generates into that language.

For a list of supported codes, see

http://sphinx-doc.org/config.html#confval-language.

> Project language [en]:

The file name suffix for source files. Commonly, this is either ".txt"

or ".rst". Only files with this suffix are considered documents.

> Source file suffix [.rst]:

One document is special in that it is considered the top node of the

"contents tree", that is, it is the root of the hierarchical structure

of the documents. Normally, this is "index", but if your "index"

document is a custom template, you can also set this to another filename.

> Name of your master document (without suffix) [index]:

Indicate which of the following Sphinx extensions should be enabled:

> autodoc: automatically insert docstrings from modules (y/n) [n]: y

> doctest: automatically test code snippets in doctest blocks (y/n) [n]:

> intersphinx: link between Sphinx documentation of different projects (y/n) [n]:

> todo: write "todo" entries that can be shown or hidden on build (y/n) [n]:

> coverage: checks for documentation coverage (y/n) [n]:

> imgmath: include math, rendered as PNG or SVG images (y/n) [n]:

> mathjax: include math, rendered in the browser by MathJax (y/n) [n]:

> ifconfig: conditional inclusion of content based on config values (y/n) [n]:

> viewcode: include links to the source code of documented Python objects (y/n) [n]:

> githubpages: create .nojekyll file to publish the document on GitHub pages (y/n) [n]:

A Makefile and a Windows command file can be generated for you so that you

only have to run e.g. make html instead of invoking sphinx-build

directly.

> Create Makefile? (y/n) [y]:

> Create Windows command file? (y/n) [y]:

Creating file ./conf.py.

Creating file ./index.rst.

Creating file ./Makefile.

Creating file ./make.bat.

Finished: An initial directory structure has been created.

You should now populate your master file ./index.rst and create other documentation

source files. Use the Makefile to build the docs, like so:

make builder

where builder is one of the supported builders, e.g. html, latex or linkcheck.

- Your directory structure should look like

├── _build

├── conf.py

├── index.rst

├── make.bat

├── Makefile

├── _static

└── _templatesWe want to edit conf.py by uncommenting (removing the hash in front of) the following three lines:

# import os

# import sys

# sys.path.insert(0, os.path.abspath('.'))The index.rst file is where our documentation will be started when we generate the HTML output. This file uses reStructuredText as its markup language to generate the documentation. I find it useful to create links to more rst files by creating new lines indented by three spaces followed by the name of the module to link to.

- In order to generate some API docs, copy the function below into a new file (dummy.py) on the same level as conf.py

def dummy_function(req, opt="I gotta have more cowbell"):

"""

dummy function does what dummies do

Args: req (required) - Int - Give me a number

opt (optional) - String - "We need more cowbell"

Return: Int - one higher than req

"""

new_number = req + 1

return new_number- Edit

index.rstand insert the following lines

.. automodule:: dummy

:members:This will tell the index file to take the documentation of our dummy function

- Finally, use the following commands. Again, there is a difference based on operating system

Windows: ./make.bat html

Linux: make html

Voila!

You should now have documentation that looks like: