Finding the day of the week given any date

by Bill Jellesma2020-08-29 20:45:00

Updates

- 20210130 - I'm on the hunt currently for a katex plugin for Scully, so all rendered equations are images.

Intro

When I was very little, I watched the episode of Malcolm in the Middle where Malcolm is able to prove that his Hal, his dad, is innocent by figuring out that all of the days in question were Fridays, a day which Hal never worked.

I remember looking up to Malcolm and admiring the mental acuity necessary to perform these mathematical novelties. Fast forward 16 years and I've now decided to take a peek behind the curtain to see how this "day of the week" trick is done. Turns out, this trick can be as easy as adding three numbers.

Why a math post?

This is a fun little formula to model with a script.

General Formula

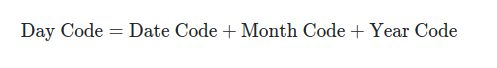

The General formula to figure out the day of week for any given date is the following:

This is always the formula for any date. ANY date. Leave your vector calculus textbooks at home because we're not going anywhere past arithmetic. In python code, it would look like this:

day_of_the_week = date_code + month_code + year_codeModular Arithmetic

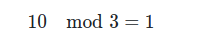

However it will also be useful to know one other piece of arithmetic not usually taught in schools, modular arithmetic. Modular Arithmetic just refers to the remainder when dividing. Most schools, when they first teach division will ask you problems like $8 / 4$ or $10 / 2$ and then hit you with a curveball like $10 / 3$. When presented with $10 / 3$, we just say that this result is 3 with a remainder of 1, or we have 3 groups of 3 and 1 extra. Modular Arithmetic is instead only interested in the remainder and uses an abbreviated mod instead of the division sign. So,

Modular arithmetic is usually associated with cryptography and similar applications but the idea of it is very simple to grasp. For those interested, khan academy has a more in depth description.

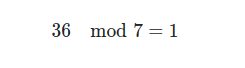

The reason that this arithmetic is useful is because our day code can easily come out to more than 7. In that case, we'll reduce the by as many multiples of 7 as we can to translate the day code to a day of the week. For example, let's say that when all is said and done, the day code comes out to 36. The following is the little equation that we'd do:

What we did is find the nearest multiple of 7, 35 and reduce 36 by that amount to 1. Here's a table showing the first 10 multiples of 7 as a reminder:

| Expression | Product |

|---|---|

| 7 x 1 | 7 |

| 7 x 2 | 14 |

| 7 x 3 | 21 |

| 7 x 4 | 28 |

| 7 x 5 | 35 |

| 7 x 6 | 42 |

| 7 x 7 | 49 |

| 7 x 8 | 56 |

| 7 x 9 | 63 |

| 7 x 10 | 70 |

Day of the week

The Day of the Week Code is very simple. Think of days_of_week_array as an array. The first seven indexes (0-6) correspond with a day of the week in the array.

| Day/Value | Number/Index |

|---|---|

| Sunday | 0 |

| Monday | 1 |

| Tuesday | 2 |

| Wednesday | 3 |

| Thursday | 4 |

| Friday | 5 |

| Saturday | 6 |

We can initialize our day_of_week array with these values. For example,

day_of_week_array = [

'Sunday',

'Monday',

'Tuesday',

'Wednesday',

'Thursday',

'Friday',

'Saturday'

]So, we can access the days in that array by using the number. To access Thursday, we would use

day_of_week[4]and to access Sunday, we would use

day_of_week[0] = 'Sunday'Month Code

The month is a little different and will require a different data structure in our computer code, a dictionary (or hashtable depending on the computer language). The following is a table that you can use to match a month name with a corresponding number for the month code. To remember this and figure it out in your head, there's also a helpful mnemonic for each month which I've found in this blog post. These mnemonics I find to be more helpful than remembering a bunch of seemingly random numbers.

| Month | Number | Mnemonic |

|---|---|---|

| January | 6 | WINTER has 6 letters |

| February | 2 | February is 2nd month |

| March | 2 | March 2 the beat. |

| April | 5 | APRIL has 5 letters (& FOOLS!) |

| May | 0 | MAY-0 |

| June | 3 | June BUG (BUG has 3 letters) |

| July | 5 | FIVERworks |

| August | 1 | A-1 Steak Sauce at picnic |

| September | 4 | FALL has 4 letters |

| October | 6 | SIX or treat! |

| November | 2 | 2 legs on 2rkey |

| December | 4 | LAST (or XMAS) has 4 letters |

The following is the dictionary that we'll use to model this data:

month_of_year_dict = {

'January': 6,

'February': 2,

'March': 2,

'April': 5,

'May': 0,

'June': 3,

'July': 5,

'August': 1,

'September': 4,

'October': 6,

'November': 2,

'December': 4

}However, there is one exception. On leap years, January and February will both have their values reduced by 1. So January will instead be 5 and February will instead be 1. In computer code, this can easily be modeled with an if-statement testing if the year is divisible by 4. This is where we'll use the modulus operation that we talked about earlier to find the remainder after diving by 4. If the remainder is 0, then the year is divisible by 4 and is a leap year). In python, the modulus operator is represented by a percent sign (%).

if year % 4 == 0:

month_of_year_dict['January'] = 5

month_of_year_dict['February'] = 1Date Code

The date code is simply the day number. So for August 27, the date code is 27. It doesn't get much simpler than that.

date_code = day_of_monthYear Code

The year code proves to be the number that's a little bit more difficult. If you've made it this far, you're certainly more than capable of figuring out this number. The good news is that this is the last number that we need so once we figure out the year code, we can put the whole formula together. The year code has different instances so we'll start with an easy one so that we can get off the ground running.

2000-2003

For these years, we simply use the number of years since 2000

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 0 |

| 2001 | 1 |

| 2002 | 2 |

| 2003 | 3 |

In python:

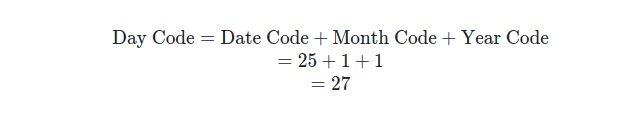

year_code = year - 2000Easy right? Ok, let's use this knowledge to go ahead and calculate a date. Let's find August 25, 2001:

- The Date Code is simply 25, the day of the month.

- The mnemonic for August is A-1 Steak Sauce so we remember the code is 1.

- For the year code, we simply subtract 2000 from 2001 to get 1.

Now, let's add all of these numbers.

Sweet! So we have the day code as 27, now for the final step.

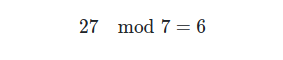

The final step is to use the modulus operator again to find the remainder after dividing by 7.

Remember, we're really just subtracting the rounded down nearest multiple of 7. The nearest multiple of 7 is 21 (even though 28 is closer to 27, we want to make this like shuffleboard and not go over). If we subtract 21 from 27, we get 6.

Representing this in python is:

day_code = day_code % 7Using the table for day codes:

| Day/Value | Number/Index |

|---|---|

| Sunday | 0 |

| Monday | 1 |

| Tuesday | 2 |

| Wednesday | 3 |

| Thursday | 4 |

| Friday | 5 |

| Saturday | 6 |

We find out that the day is a Saturday.

In python, we simply find the index of the day_of_week_array that we declared earlier.

day = day_of_week_array[day_code]A quick Google Search finds that the day is...

Saturday

Here's the entire python script that we've been making:

year = 2001

month = 'August'

day_of_month = 25

# Translate the days of the week to an array

day_of_week_array = [

'Sunday',

'Monday',

'Tuesday',

'Wednesday',

'Thursday',

'Friday',

'Saturday'

]

# Translate the month of the year into the month code

month_of_year_dict = {

'January': 6,

'February': 2,

'March': 2,

'April': 5,

'May': 0,

'June': 3,

'July': 5,

'August': 1,

'September': 4,

'October': 6,

'November': 2,

'December': 4

}

# Account for months in leap years

if year % 4 == 0:

month_of_year_dict['January'] = 5

month_of_year_dict['February'] = 1

# Find the month code given the month

month_code = month_of_year_dict[month]

# Date code is simply the day of the month

date_code = day_of_month

# Finding the year code, we subtract 2000

year_code = year - 2000

# General Formula

day_code = date_code + month_code + year_code

# Use the modulus operation to get the index with the bounds

day_code = day_code % 7

# Find the day of the week given the code

day = day_of_week_array[day_code]

print(f'The date of {month} {day_of_month}, {year} is/was {day}')Notice that I've added in some comments before the expressions to tell the user what is happening. I'm also string interpolation to create the print statement at the bottom. Both of these are formatting decisions and are not strictly necessary.

Running this script yields the result,

The date of August 25, 2001 is/was SaturdayLeap Year 2000

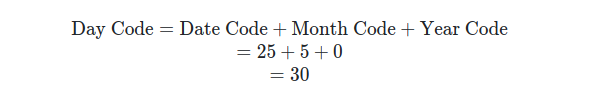

Calculating the day of the week for January 25, 2000 is a leap year so remember that we have an exception for the month code on leap years. The mnemonic that we normally use for January is winter has 6 letters therefore January is 6. The leap year exception is that we subtract 1 from January and February. We find that the month code for January 2000 is 5. We also find that the date code is 25 and the year code is 0 because 2000 - 2000 is zero.

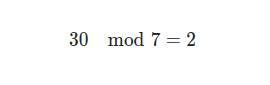

Remembering that the nearest multiple of 7 to 30 is 28

Using the day of the week table, we find that the day of the week is Tuesday. We can also verify this in our script if we use the date in the year, month, and day_of_month variables.

year = 2000

month = 'January'

day_of_month = 25

# Translate the days of the week to an array

day_of_week_array = [

'Sunday',

'Monday',

'Tuesday',

'Wednesday',

'Thursday',

'Friday',

'Saturday'

]

# Translate the month of the year into the month code

month_of_year_dict = {

'January': 6,

'February': 2,

'March': 2,

'April': 5,

'May': 0,

'June': 3,

'July': 5,

'August': 1,

'September': 4,

'October': 6,

'November': 2,

'December': 4

}

# Account for months in leap years

if year % 4 == 0:

month_of_year_dict['January'] = 5

month_of_year_dict['February'] = 1

# Find the month code given the month

month_code = month_of_year_dict[month]

# Date code is simply the day of the month

date_code = day_of_month

# Finding the year code, we subtract 2000

year_code = year - 2000

# General Formula

day_code = date_code + month_code + year_code

# Use the modulus operation to get the index with the bounds

day_code = day_code % 7

# Find the day of the week given the code

day = day_of_week_array[day_code]

print(f'The date of {month} {day_of_month}, {year} is/was {day}')The script will work for any date between 2000 and 2003. Now, we can move on to figure out the day for any date in the 21st century.

2000-2100

Before we figure out dates for the 21st century, remember that the rules for the day, date, and month codes are the exact same so all that's new is the year code. To figure out the year code for the 21st century, we'll need to learn the twelve year cycles first. The rule for every 12 year cycle in the 21st century is that, after subtracting 2000, we'll divide by 12 on the year.

| Year | Expression | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0/12 | 0 |

| 2012 | 12/12 | 1 |

| 2024 | 24/12 | 2 |

| 2036 | 36/12 | 3 |

| 2048 | 48/12 | 4 |

| 2060 | 60/12 | 5 |

| 2072 | 72/12 | 6 |

| 2084 | 84/12 | 7 |

| 2096 | 96/12 | 8 |

We'll just add an extra step for the year code so it's

year_code = (year - 2000) // 12The double division sign (//) operator ensures that year code comes out to a whole number rather than a decimal.

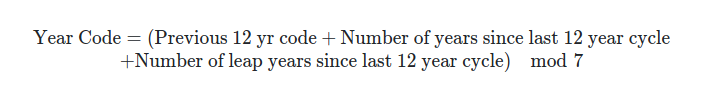

Now we can introduce the general formula for 21st century year codes. This formula will also be used later to get dates in other centuries.

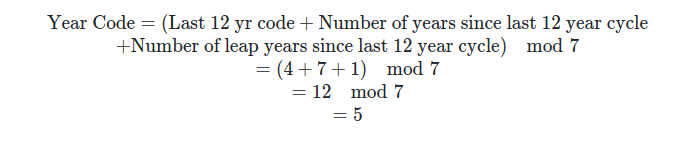

Let's walk through getting the year code for 2055

- The last 12 year cycle is 2048 and 48/12=4

- The number of years since the last 12 year cycle is 55-48=7

- The number of leap years since the last 12 year cycle is 1

- Adding 4, 7, and 1 gives us 12

- Familiarly, we're using modulus 7 on 12. Since the nearest multiple of 7 to 12 is 7, we do 12-7=5

- The year code is 5!

Putting this into mathematical language,

To model this in python, I've chosen to get the components individuly and then did mod 7 at the end. To get the number of leap years since the last cycle, I'm using whole integer division again. And the find the years since the last cycle, I'm using the modulus operator to divide by 12 and take the remainder.

base_year_code = year - 2000

previous_12_year = base_year_code // 12

years_since_cycle = base_year_code % 12

num_leap_years = years_since_cycle // 4

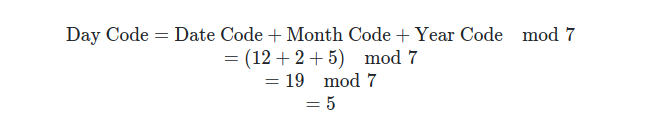

year_code = (previous_12_year + years_since_cycle + num_leap_years) % 7Now, say we were doing February 12, 2055, we have

5 translates to Friday!

Finding year codes for other centuries

Now that we have the new formula for the year code under our belts, we're a stone's throw away from being super cool and telling people what day their birthday was on. We just need a few more facts.

- Those pesky year codes actually do repeat themselves... every 400 years

- We just need to add 1 number for the different centuries since the last 400 year cycle

| Years since last 400-year cycle | Century Code | |---|---|---| | 0-99 | 0 | | 100-199 | 5 | | 200-299 | 3 | | 300-399 | 1 |

You've probably noticed that the pattern for the 4 centuries between these cycles is just in descending order for odd numbers starting with 5. The one exception is that the 4th century adds 0. For example, the century code for 1600-1699 is 0, 1700-1799 is 5, 1800-1899 is 3, and 1900-1999 is 1. For 2000-2099, the pattern starts over and the century code is 0. This is why when we were learning the revised formula for year code, we used 2000-2099, because the century code is 0 and doesn't factor into the formula.

If, when calculating a date in another century, we translate the year to a year in 2000-2099 and then add the century code at the end, we'll have figured out how to calculate any date and, thus, won at life.

This little bit of math may actually be easier to calculate in one's head then translate to computer code. In python, I've added a translation to get this date in the 21st century. This works if the date you're trying to get is greater or less than the 21st century because we'll add a translation which can be positive or negative. I've also use a "switch" statement to get the century code by finding the remainder after diving by 4. I put switch statement in quotes because there technically is no switch statement in python. I wrote a previous article on this here.

# Translate the year to a year in the 21st century

centuries = year // 100

translation = (20 - centuries) * 100

base_year_code = (year+translation)-2000

# Find the century code needed

century_code = (

0 if centuries % 4 == 0 else

5 if centuries % 4 == 1 else

3 if centuries % 4 == 2 else

1 if centuries % 4 == 3 else

0

)I've also modified the year_code assignment to be the following

year_code = ((previous_12_year + years_since_cycle + num_leap_years) % 7) + century_codeThe entire year section now looks as the following

# Translate the year to a year in the 21st century

centuries = year // 100

translation = (20 - centuries) * 100

base_year_code = (year+translation)-2000

# Find the century code needed

century_code = (

0 if centuries % 4 == 0 else

5 if centuries % 4 == 1 else

3 if centuries % 4 == 2 else

1 if centuries % 4 == 3 else

0

)

# Finding the year code involves finding the last 12 year cycle

previous_12_year = base_year_code // 12

years_since_cycle = base_year_code % 12

num_leap_years = years_since_cycle // 4

year_code = ((previous_12_year + years_since_cycle + num_leap_years) % 7) + century_codeLet's walk through my birthday, October 28, 1991.

- The month mnemonic is six or treat so the month code is 6.

- The date code is 28.

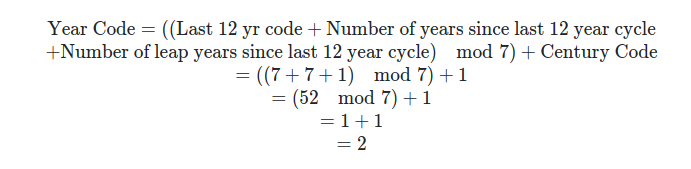

- Think of 2091 instead of 1991.

- The last 12 year cycle is 2084 and 84/12=7

- It's been 7 years and 1 leap year since 2084

- 7+7+1 is 15

- The closest multiple of 7 to 15 is 14 so we subtract 14 from 15 to get 1

- Since 1900-1999 is 3 centuries from the last 400-year cycle, we need to add a century code of 1 so we have 1+1=2 for the year code.

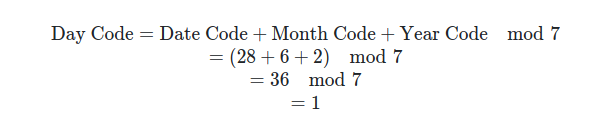

- Adding the month code of 6, the date code of 28, and the year code of 2, we come up with a date code of 36.

- The closest multiple of 7 to 36 is 35

- Subtracting 35 from 36 gives us a final day code of 1 which translates to Monday

Let's put this in some quick mathematical language too. First, we'll get the year code

Now for the general formula

The math-speak also gives us Monday!

That's it, we've now learned how to get the date of any year. The final script now looks like this:

year = 1991

month = 'October'

day_of_month = 28

# Translate the days of the week to an array

day_of_week_array = [

'Sunday',

'Monday',

'Tuesday',

'Wednesday',

'Thursday',

'Friday',

'Saturday'

]

# Translate the month of the year into the month code

month_of_year_dict = {

'January': 6,

'February': 2,

'March': 2,

'April': 5,

'May': 0,

'June': 3,

'July': 5,

'August': 1,

'September': 4,

'October': 6,

'November': 2,

'December': 4

}

# Account for months in leap years

if year % 4 == 0:

month_of_year_dict['January'] = 5

month_of_year_dict['February'] = 1

# Find the month code given the month

month_code = month_of_year_dict[month]

# Date code is simply the day of the month

date_code = day_of_month

# Translate the year to a year in the 21st century

centuries = year // 100

translation = (20 - centuries) * 100

base_year_code = (year+translation)-2000

# Find the century code needed

century_code = (

0 if centuries % 4 == 0 else

5 if centuries % 4 == 1 else

3 if centuries % 4 == 2 else

1 if centuries % 4 == 3 else

0

)

# Finding the year code involves finding the last 12 year cycle

previous_12_year = base_year_code // 12

years_since_cycle = base_year_code % 12

num_leap_years = years_since_cycle // 4

year_code = ((previous_12_year + years_since_cycle + num_leap_years) % 7) + century_code

# General Formula

day_code = date_code + month_code + year_code

# Use the modulus operation to get the index with the bounds

day_code = day_code % 7

# Find the day of the week given the code

day = day_of_week_array[day_code]

print(f'The date of {month} {day_of_month}, {year} is/was {day}')