Unit Testing

by Bill Jellesma2021-12-04 1:00:00

Why Unit Test?

Unit Testing is used to test that one specific method of your software will do exactly what it is intended to do and will give you the exact output that you'd expect. Writing the method ensures that that one specific method of your software will do exactly what it is intended to do and will give you the exact output that you'd expect.

Often a test is written after writing the original code and can feel like you're doing the exact same steps over again. The only difference is that for the test, you also need to think in the mindset of how can this method be used by the system or user and what edge cases do you need to cover. Do you need to cover the case where the method is passed an unexpected data type? What if the method is passed the right data type but it's too many characters or not enough? Because of the added complexity as well as the time it adds to the developer already "under the gun" to ship software, unit testing often gets left out of the equation. This may be a con of unit testing.Unfortunately, this is not always a good approach.

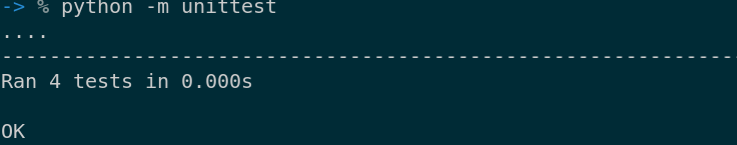

Unit test frameworks provide the awesome ability to quickly run tests. This is a very big deal!

Quickly testing is a huge advantage of unit testing

Let's use an example to illustrate the advantage of testing. We'll use the unittest library for python. This is in the standard library of python which means you don't need to install anything other than python to make this work.

First, let's define the directory structure.

unitTesting

|___calc.py

|___test.pyBelow is our python file to do our basic calculations.

calc.py

We want to write a couple of simple unit tests to quickly test that our program will work before we give it to a user and they feed some input into these functions that you're not expecting. Below is the code.

test.py

A few points.

import unittestwill import theunittestlibrary so that our class can inheritunittest.TestCasewhich is what's needed to write a unit test. Because of this inheritance, all testing methods will also have a parameter calledselfthat will allow us to useassertstatements defined inunittestimport calcwill import ourcalc.pyfile that we've written above to perform our calculations. This is needed so that inside the testing methods, we can access the methods incalc.pyusingcalc.<method_name>where<method_name>is the name of the method we want to test.self.assertEqual()is the method that we're calling at the end of the testing methods to ensure thatresis equal to the expected value. There are serveral moseassertstatements that you can find in the official documentation

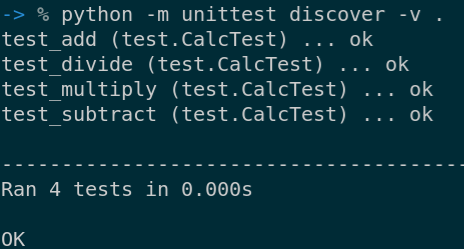

On the terminal, navigate to the unitTesting directory and run the following command.

When unittest is specified with no sub-command, it will automatically run its default sub-command called discover that automatically detects any files starting with test in the file name. I personally like to use the following command to specify the individual tests that are run.

- The

-margument will load a module, in this case theunittestmodule. discoveris a sub-command ofunittestthat must be specified if we want to use arguments to test discovery.-vis a command line argument that will load in verbose mode.- The dot at the end (

.) is shorthand that refers to the current directory.

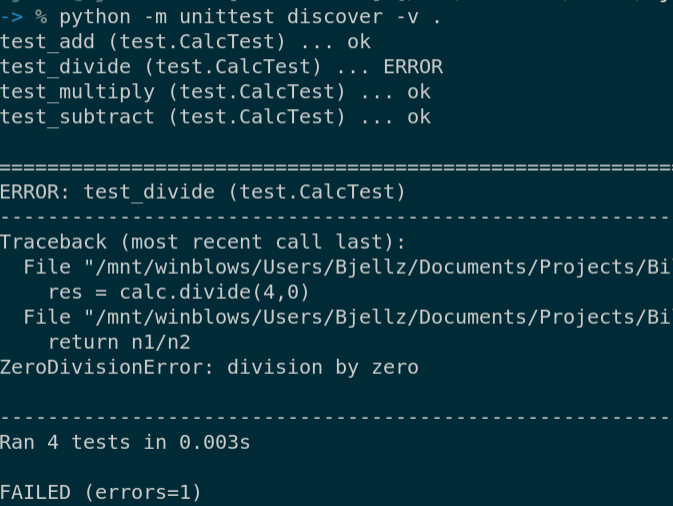

Now, here's the kicker, what if some smartypants user comes by and tries to use our program to divide by zero. We can modify our test_divide method to simulate this error.

test.py

We can rerun the test by simply repeating the command python -m unittest discover -v .

Phew, good thing we discovered this in testing before shipping this into production. Now this is a game where we want to write code that is able to pass this code.

We can simply rewrite our divide method as the following to raise a custom exception when we divide by zero.

calc.py

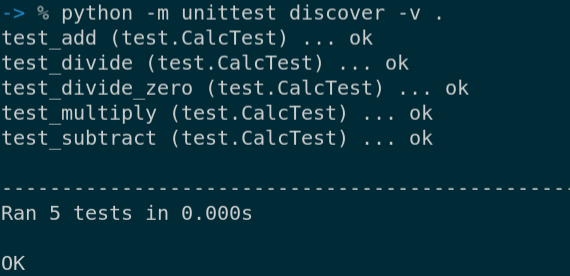

Now, we'll set our test_divide back to it's original definition and write another unittest to handle this case using the assertRaises() method

test.py

Notice that because we need to be checking for a certain exception type when we're performing an action, we need to use the with keyword.

Now, here's where the real advantage of unit testing comes into play. Let's say that some new hotshot math genius has come along and has changed the definition of addition, they're now saying that you actually ignore any subsequent numbers in the expression and instead just add the first number again. For example, the expression 2+3 will now be 2+2

We'll need to adjust the definition of our add() method.

calc.py

Thinking ahead of how this will fail our add() method, we'll also adjust our test_add() method.

test.py

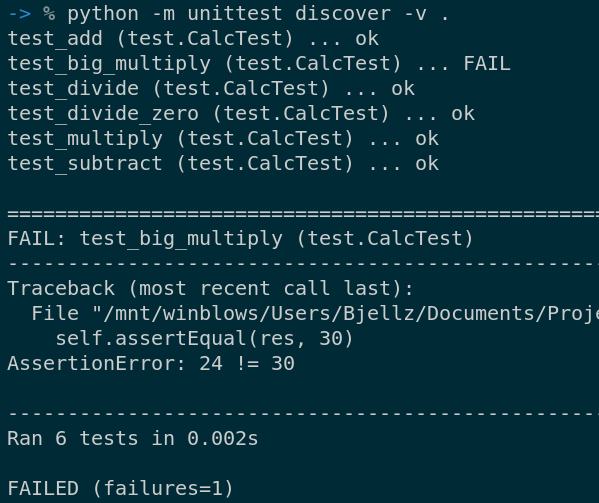

Now, we'll rerun our tests to make sure that nothing else broke.

Oh, we forgot that we had a big_multiply() method that also broke because we changed the definition of add(). Thank goodness we ran the tests again!

Silly example aside

The above example was, of course, a silly example where the mathematical definition of addition has changed. But think about how this silly example could turn into you wanting to refactor some old code or multiple teammates working on a codebase. How can you be confident that refactoring a 3 year old code base won't break something? If someone on your team or another team wrote a module where you need to change the definition of it, how can you be sure that you won't end up causing more errors than you're trying to fix? No matter how much documentation and manual testing you do, you can't know what a developer from 3 years ago (or yourself 3 days ago) was picturing when they wrote the code. This is where writing unit tests with your code will help.

Putting an emphasis on writing unit tests WITH your code is important. If you put off writing unit tests until a few days after you write the actual code when you're not "under the gun", you're taking a risk that you'll remember exactly what you were envisioning when you wrote the code or even forgetting to write the unit tests because you're immediately thrown into the next task.

Time Investment

This also brings up the idea of time investment again. By not writing a unit test, you saved yourself an hour let's say. Unfortunately, when your coworker wanted to refactor the codebase including your code that you wrote 3 years ago, errors come up. After 3 hours of stressful debugging, you've found that the source of these errors came from your code that you've written those 3 years ago. In this simple example, you've saved 1 hour 3 years ago but added 3 hours when it came time to refactor. Overall, you've added 2 hours to the project by not writing a unit test.

What if your code was deeply entwined in 8 other methods and it took another 2 hours to figure out those methods were failing because of your code? Now that 2 hours you've added turns to 4. You see how the number of hours you've added by avoiding writing a test will continue to grow.

Coming off my high horse

Unit Testing is not the be all end all solution to eliminating all bugs when developing software. Unit Tests are only as good as you write them. In the above example, we didn't need to write a unit test for dividing by zero. If we didn't write a unit test that divides by zero, everything would have still passed. But we knew from grade school that it's a case that would result in an error. Furthermore, a zero would get input to the method at some point in some unexpected way.

This thinking of testing edge cases can also lead you into a hole of "I don't know what case can break our code" or "How do I get any work done if I spend the next several hours writing unit tests of obscure edge cases". This comes down to the law of diminishing returns. You can start out writing unit tests that will test 99% of use cases but then you'll be scraping the bottom of the barrel to find the most obscure use cases you can possibly think of. A good rule to follow that I've been taught is to create 2 unit tests. One unit test makes sure that you get the expected output and one unit test makes sure that you don't get unexpected output.

For example, we can instead have two unit tests for the add method. In one test, we ensure we get 5 and in another test with the same input, we ensure that we don't get -3.

test.py

This helps make sure that your add() method isn't giving 5 every time. Specifically with numbers, we can also check that negatives work correctly with addition.

test.py

These four test cases (which took about 2 minutes to write) will test 99% of cases.

Remember

No matter how much you test, there will always be an unknown.